Begin to see how this can be possible in YOUR organization

Incidents in complex, high-risk organizations can occur without warning, at any place and at any time. At best, they cause minor disruption, with a simple corrective action being all that is needed to get things back on track. At worst, they result in workforce fatalities, cause millions of dollars of financial damage to facilities and nearby areas, create unmeasurable environmental damage, and deliver psychological effects to employees and their families for years to come.

Described below are three industrial incidents, ranging from a deadly refinery disaster that claimed the lives of 15 workers, to an isolated mishap resulting in a fractured leg, to a near miss that could have been much worse. While these incidents are seemingly unrelated, deeper analysis into causal factors uncover matters of culture and leadership that provide a powerful influence on individuals decisions and actions.

Refinery Restart

In 2005, a crew at BP’s Texas City refinery worked to restart the plant unaware that 15 people would never see their families again and more than 200 lives would be deeply changed recovering from injuries in what would become the deadliest industrial accident in US history.

An early investigation assigned the cause to negligence of the front-line operators and supervisors in their failure to follow procedures. Subsequent reports found that the disaster was caused by organizational and safety deficiencies at all levels in BP. Two serious incidents just months before revealed the extent of these deficiencies, yet no real action was taken to understand the driving factors in why these incidents occurred.

A report by the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board found that because the Texas City refinery experienced a very low personal injury rate, that BP operator’s and supervisors were misled into thinking that process safety performance was adequate.

Oil and Gas Operator

A well support technician working for an oil and gas operator on Alaska’s North Slope suffered a fractured leg while attempting to position a 40-foot section of hardline in an indoor workshop. Extreme cold conditions caused several smaller 10-foot sections of pipe to freeze together, and the decision was made to move the combined section indoors to thaw. The long section could not be carried by a front loader directly into the shop, so the crew improvised by placing a fork on one end of the pipe to push and slide it into place.

While maneuvering the pipe into the shop, one of the hammer unions that connected the 10-foot sections became snagged in a gap between the entrance ramp and the shop floor. The pipe flexed and bowed out under tension, then sprung back into place as the hammer union slipped off the gap. The front end of the pipe swung across the shop floor, striking the well support technician and fracturing his leg. An analysis of the accident found that a workplace “get it done” culture built upon a sense of urgency, encouraging workarounds and emphasizing production at any cost steered the decisions made by the employees that led to the technician’s fractured leg.

Chemical Manufacturing Plant

A complex chemical manufacturing plant with several commodity products and some extremely dangerous ingredients in high volumes experienced an uncommanded release of organic solvent. During an internal investigation, they found a technician had signed off on several steps during post-maintenance return-to-service work. The technician had not done the work himself, but instead understood, based on verbal (mis)communication, that his colleague had done the work. Furthermore, he did not visually confirm the work was done.

As it turned out, a valve was left open. When flow of the solvent was restarted, the result was an uncommanded discharge, discovered several hours later. The technician who signed off the work as complete was disciplined and the incident was handled in a straightforward manner.

The Pursuit of Operational Resilience

In each scenario above, human error played a significant role in the outcome. In recent years, safety leaders worldwide have documented a high incidence of human contribution and causes in incident and accident investigations. It is our belief that most process safety incidents are caused by human error.

Learning organizations study this with a focus on the system of operations we employ and how human error is produced and transmitted within it. From this, leaders can design resilient barriers that recognize and respond to human error before it creates an unsafe situation. Investigations of mistakes and violations by individuals are just the beginning. They are the window we must look through to find antecedents and hidden influences that create a pathway for error to become an incident.

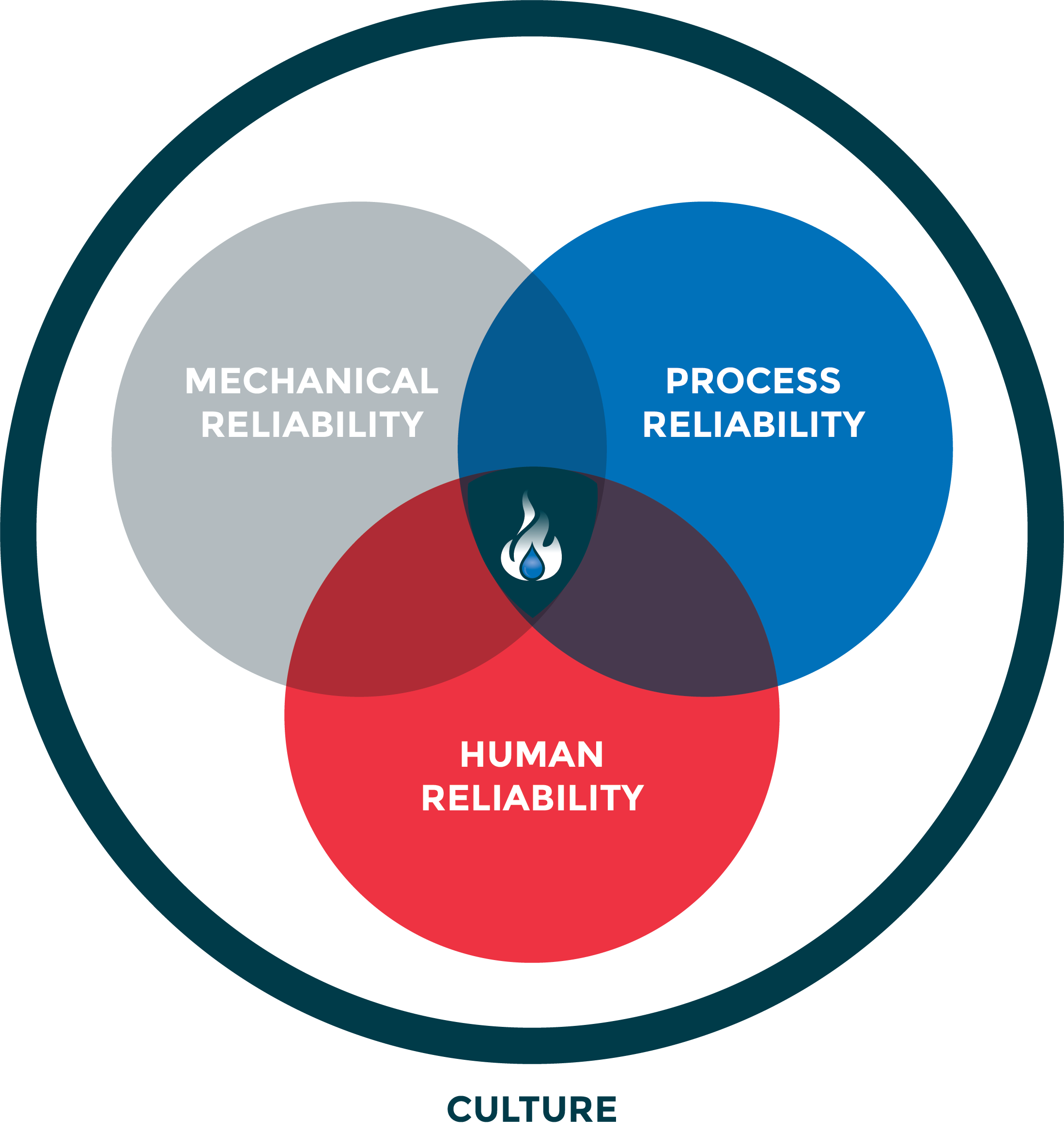

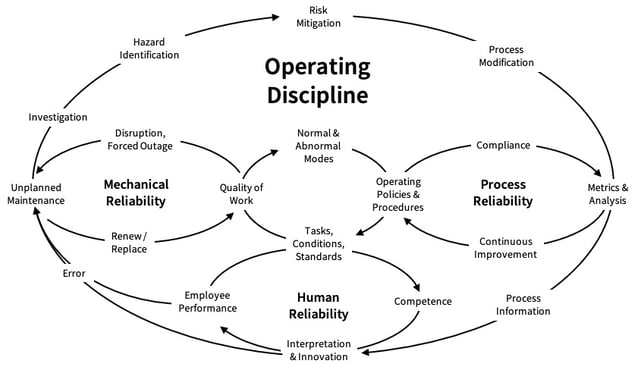

What follows below is a journey that learning organizations must take to understand, build and sustain a culture of Operational Resilience, where productivity, profitability and safety are concurrently linked. The pursuit of Operational Resilience is to form, measure, sustain and improve a system involving human beings that interact with equipment in an environment. A resilient system responds predictably and reliably to disturbances in order to achieve its objectives.

When operations are resilient, the system is optimized for profitability and safety. Our services are focused on assessing operations to measure and improve operational resilience including Human Factors Analysis, leadership and cultural development, procedure modernization, competency development, training and coaching.

In high-reliability organizations, error can have devastating consequences on people, operations and the environment. Breaking through safety plateaus starts with a discovery phase to help your organization understand how humans behave and act, and their contribution to failures.

Many accident investigations attempt to place blame by locating the component that came apart or identifying the person that failed to follow procedures. This often leads to an engineering modification to eliminate a design flaw, a new training class to beef up skills and knowledge, or a reprimand of the individual on the front line for the role he played in causing the mishap to occur.

This type of immediate cause analysis can only prevent the identical incident from happening again. What is commonly overlooked and often ignored is the role that humans play and how bad individual decision making can lead to a higher incident rate, substandard safety performance and lower productivity and output at all levels of the organization.

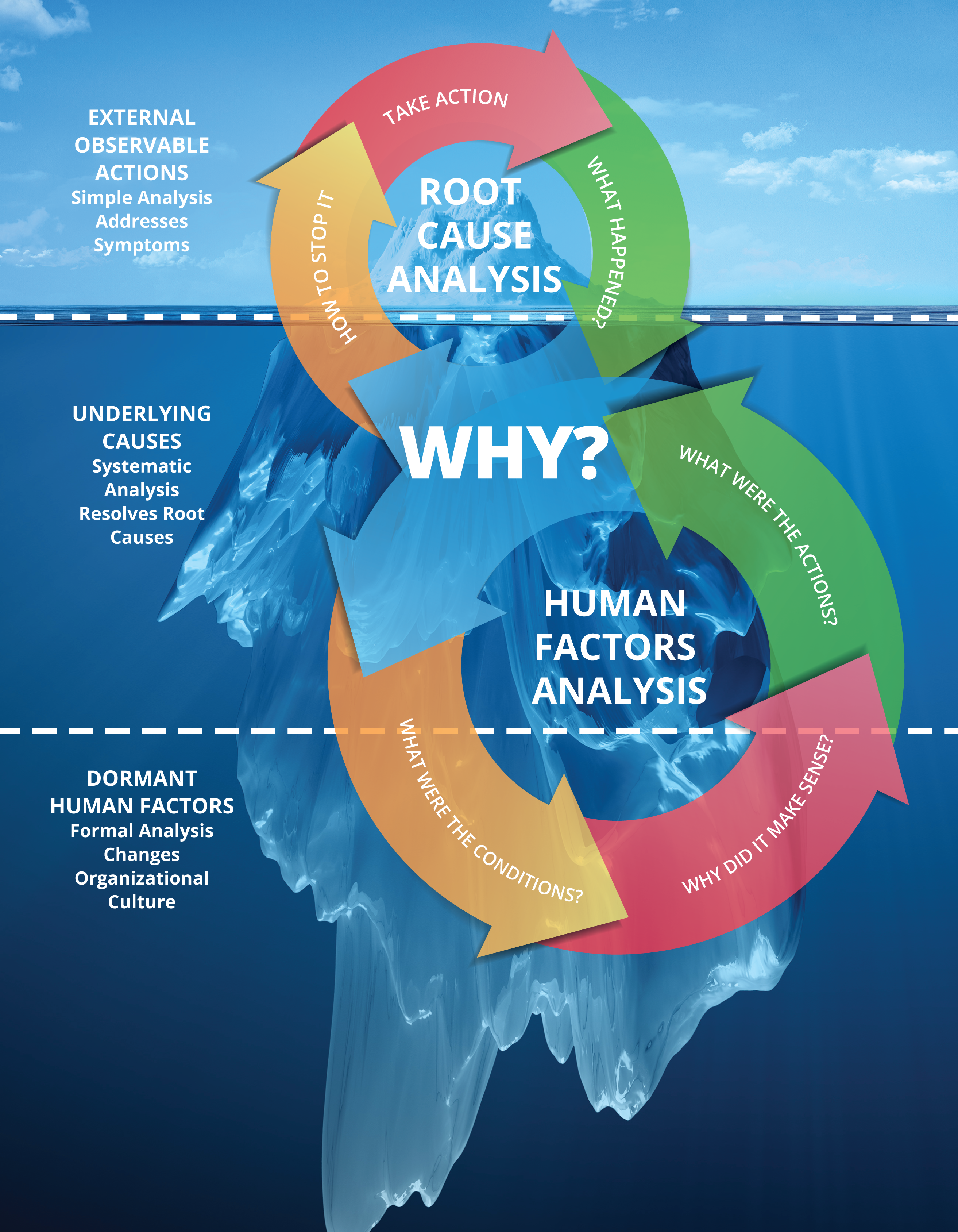

Human Factors Analysis Explained

Recent studies indicate that up to 90% of mishaps and incidents are due to human error, and that 100% of incidents involve some form of human factors.

Human factors analysis is designed to expose the role that humans play in accidents, incidents, high-potential events and near misses. It teaches that error is not failure.

In truth, human error can be an organizational resource for creating reliability, improving operations and attaining resilience. Wrongly, we presume that if we can eliminate error, we will eliminate failure. This mindset permeates the very fabric of an organization and creates friction between leadership and delivery. By exposing and analyzing human factors in their operations, organizations can take corrective action to prevent reoccurrence and improve operational efficiency and safety.

The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) provides a framework to assist in the investigation process and identifies the human causes of accidents. HFACS has its roots in military and commercial aviation communities seeking to understand the human influences in failure. Due to the exceptional success in improving safety and operational performance, this approach to human factors analysis has become a model for all industries seeking to achieve highly reliable and resilient operations.

HFACS is based on the Swiss Cheese model of accident causation, originally proposed by James Reason in 1990. In Reason’s model, an organization’s defenses against failure are modeled as a series of barriers, represented as a series of slices of cheese. The holes in the cheese slices represent flaws in the system and are continually varying in size and position. The system produces failures when holes in all the slices momentarily align allowing a hazard to become an accident.

Root Cause Analysis: A Common Approach

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is a popular and common approach that organizations use to uncover reasons why problems and incidents occur. RCA seeks to determine the origin of problems using specific steps to find out what happened, why it happened and what you should to do reduce the likelihood of the problem occurring in the future.

The popularity of RCA has led to the development of different methods incorporating different tools, processes and philosophies. Methods such as the 5-Whys, Fishbone Analysis, Cause and Effect Analysis, or Fault Tree contributing issues and events, determine root causes, identify recommendations for eliminating or mitigating the problem from reoccurring, and implement the solutions.

Common RCA incident investigation methods seek to derive a cause and effect relationship between failure points, adding up to a cumulative result that is traceable to its origination. Where RCA falls short is that is fails to factor how humans behave and act. RCA-based investigations can sometime leave you with unanswered questions and incomplete resolution. Introducing the HFACS taxonomy and process into incident investigations helps determine the human contribution and causal relationships. This is essential to understand why incidents occur and how to prevent them in the future.

Culture and Climate

The role of culture is often glossed over during incident investigations. Yet culture is a powerful influence on an individual’s decisions and actions. Digging deeply into causal factors inevitably touches on matters of culture and leadership. Evaluating an organization’s culture provides insight into operations and exposes valuable opportunities for preemptive intervention. It’s common for leaders and managers in an organization to sense that culture may play a factor into incidents and mishaps, but leaders frequently have not been armed with the language or tools to support an explanation of the cultural factors. As a result, gaps in responsibility and execution can be missed.

Culture climate surveys help to determine how and why an organization’s employees make decisions and perform actions, and how they treat each other. Culture begins with the beliefs, values and actions of corporate leaders. It continues with communication styles and reward systems, which lead to broad operational norms and behaviors. The credibility and consistency of a management team’s communication compared to their beliefs gives true insight into the true values influencing their decision making.

Operational Assessment

Operational assessments are conducted to expose each component of the system, evaluate effectiveness and, where necessary, identify areas for improvement. Designed to study the interfaces between people, process, and leadership, operational assessments identify gaps, deficiencies or lapses in the attributes of operational resilience. Assessments are typically conducted through a series of interviews or focus groups, or by attending meetings along with onsite observation of operations. Focus groups and engagement is essential to provide feedback on perspectives and potential solutions for consideration. An operational assessment helps management teams understand and correct human behavioral, leadership and cultural drivers that affect performance.

Leadership is a broadly researched and widely sought-after organizational competency. Leadership is about results. Leadership distills to a pattern of individual contributions to organizational behavior from which performance outcomes emerge. It is the process by which senior management can guide and influence the behavior and work of others towards accomplishment of specific goals. For leaders to be successful, they must have a solid foundation in place from which to work.

Leadership Development and Coaching

Good leadership is the cornerstone to operational resilience. No program will realize its full value without the commitment, resolve and example established by all levels of leadership. Leadership is not an innate ability, but is learned through experience, training and mentorship. Through our unique leadership program and coaching, you will come to understand leadership from a systems perspective, gain a broad perspective of performance-driven leadership and ultimately, will recognize the necessary building blocks of becoming an effective leader.

Sound leadership development programs leverage modern assessment tools to establish a baseline and configure programs. Management teams that embrace leadership development and coaching programs often find that they can spend more time focusing on forward-thinking and strategic leadership and less time on tactical response. They realize cost savings associated with a reduction in personnel injury, equipment damage, business impact and environmental response and cleanup. They enjoy an overall increase in leadership depth for use in succession planning and find that the organization ultimately benefits from increases in productivity and profitability.

Culture Workshop

A Vetergy Group Culture Workshop initiates foundational change in the way an organization approaches the human element of its operations. You learn from real-world successes and failures of others. Most importantly, you see clearly how these ideas are relevant to your organization.

Organizational transformation begins with one critical step; overcoming business-as-usual with a meaningful vision and a compelling reason for change. The need for change, on the other hand, has very different value to diverse individuals, teams and functions within the organization. Top-down driven plans struggle to trigger essential passion and ownership throughout the diverse business to achieve lasting change.

A purposefully healthy culture, measured and led, set up to self-perpetuate, emerges from committed attitudes and values of individuals and groups that make choices with real consequences. Your goal is to activate the change story in a bottom-up manner by accessing the voice of the organization. You will learn how to join cross-functional agents in a facilitated workshop setting to probe some basic views of the operation, human reliability and operational resilience.

You are introduced to human error as a tool for improving operational resilience. We find that, as a rule, people do not set out to cause failure; rather, they aim to contribute to the larger success of their organization. Nevertheless, as part of a multi-dimensional operating framework, individuals are sometimes shepherded by complex events into making decisions that instead contribute to failures.

We view organizations as complex systems with emergent behavior, unforeseen from a reductionist view of individuals’ behaviors. Instead of blaming individuals for error, we ask why the system responded the way it did.

Human error is inevitable and serves as a symptom of systemic failure. As with all symptoms, it becomes a signal spurring the need for systemic change. The idea is to welcome human error as an indication that leadership should investigate the dark, murky, uncomfortable cultural issues that made the error seem like a good idea at the time.

In a Vetergy culture workshop, you learn from real-world successes and failures of others. Most importantly, you see clearly how these ideas are relevant to your organization.

Transforming an organization begins with a desire to improve. It requires a discarding of past failures as you travel on the path to organizational transformation. Ownership and accountability begin with the leadership team, and the desire to improve and perform at high levels filters down as the culture of leadership permeates every part of your workforce. Workers feel empowered, are confident in their abilities, and strive to meet common goals and objectives.

The Role of Culture in High-Reliability Organizations

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” a quote accredited to Peter Drucker argues that strategy is theoretical where culture determines how things get done. Formulating meaningful strategy is simple, but building a high performing culture is hard. An inspired strategy without a great culture is meaningless while a resilient culture can succeed even if its strategy is unexceptional. Plus, it is much easier to change strategy culture.

A countering argument is that culture simply enables strategy. In application, both are important, interdependent and self-perpetuating. There are practical and measurable ways that leaders can shape culture and its impact on operations. Culture is a set of shared values, norms and perceptions that inform expectations, assumptions and decision making, which can be good or bad. Culture can also magnify blind spots.

Generally, High Reliability Organizations (HRO) acknowledge the existence of subcultures within the large organizational culture. Even though these subcultures may be in varying degrees of conflict, they are more adaptable to ambiguity through variety and diversity. By understanding these subgroup value systems and the interactions between them, leaders can profoundly shape culture and performance.

Organizations often develop a “get it done” or a “can do” approach to operations. This operating mindset is likely a product of past growth and innovation periods reinforced by otherwise successful and productive operations by an experienced workforce. While these cultures are results-oriented and are driven by a deep desire to do what seems right, this can easily lead to failure by people that are unarmed with either the information or the training to make good decisions.

Another common cultural value is trust. Coworkers in organizations tend to trust one another implicitly and for good reason. But this can lead to serious repercussions: if directing a peer is seen as mistrusting the peer’s competence, neither coworker is understood to have the lead which begs the question of who is really in charge.

Competence Assurance

Competence can be defined as the consistent application of knowledge and skills to a standard of performance required in the workplace. It embodies the ability to transfer and apply skills and knowledge to new situations and environments.

An effective competency assurance program uses formal systems, tools and processes to ensure personnel are competent to complete assigned tasks to an expected standard. Competency-based training instills confidence in your organization’s personnel.

Assuring workforce competence is paramount to creating resilient operations. A hallmark of High Reliability Organizations is found in acknowledging the system’s imperfection and thus mandating programs aimed at reducing the risk of error and mitigating it’s potential to lead to failure.

Individual competence is threaded through an employee’s lifecycle, from identification, selection and onboarding to the strategic levels of leadership. Whatever their contribution to successful operations, everyone must be competent to optimize the system and drive excellence into the culture.

Competency-based training and assurance programs are an effective approach towards ensuring workforce competency, standardizing process and communicating objectives and expectations across an organization. Competency assurance programs to deliver and manage individual and technical behavioral competencies are established at the organizational level.

Done well, programs to identify, define, assess, remediate, develop, and manage the continuous competence of personnel realize direct and indirect benefits. Among these are increased productivity, improved personnel and environmental safety, enhanced organizational learning and higher morale and retention.

Most organizations fall short by not completing the final (and most meaningful) step from training management to competency assurance. Competence cannot be inferred from training alone, even more so from knowledge without context. While training programs aim to deliver knowledge, skills and attitudes required to perform a job, competence is the recognizable act of performing a task successfully. More importantly, competence cannot be inferred from experience. While experience is an important component of developing competence, experience in an of itself does not translate to competence.

An effective competency assurance program utilizes formal systems, tools and processes to ensure personnel are competent to complete assigned tasks to an expected standard. Competency based training instills confidence and creates a more permissive environment and a measured need for more assertiveness. When skills are based on experience, younger, less experienced workers tend to defer to the more tenured workers to validate their work and withhold otherwise valuable perspectives.

Procedure Modernization

A common outcome of an incident investigation is to find that employees are not following procedures. This could occur for several reasons. In the BP Texas City explosion, it was found that operators consciously deviated from startup procedures because they were thought to be out of date. In the chemical manufacturing plant incident, technicians knew they were not following the sequence outlined in the procedure, but they felt they were doing what made sense at the time. Shared habit patterns, and a history of no negative consequences (yet) naturally reinforce bad habits. Eventually, statistics catch up, and bad habits surface as glaringly poor decisions, sometimes with dire consequences.

Procedure modernization programs can drive a broad improvement in your organization and further efforts to attain systemic reliability. Procedure modernization uses industry-standard templates to identify, document and input each procedural step. Each statement describes an expected system response, shows how to determine if a step or task has been done properly, and details potential consequences associated with errors and omissions. Procedure statements are written using standard terminology to provide clear, concise instructions supplemented by relevant pictures and diagrams.

Clear, dependable work standards provide the foundation for systemic reliability of assets, process, and people. Well-defined work standards bridge the gap between organizational core competence and results. Equipment manuals, technical practices and standard procedures outlining operating modes, specifications, and limits provide the source for managing risk, assuring competence, recording compliance, and establishing organizational learning.

Putting it all Together for Enduring Change

Practical and measurable progress towards achieving operational resilience and human reliability is achieved through a systematic and quantifiable institutional method that acknowledges the influence of human factors. Success is realized when competent people are given clear tasking to operate proper equipment in a controlled environment while being provided with accurate information and directed by effective leadership and supervision. Operational resiliency is the product of managed risk of human error. Resilient operational performance illustrates the aim of finding the balance between safety and productivity.

The principles we practice at Vetergy Group draw on experience and best practices from military and commercial aviation, special operations, Navy nuclear power and propulsion, NASA and oil & natural gas exploration. We employ a set of defined steps to introduce or improve resilience in the culture and operations of high reliability organizations. Our programs deliver a top-down institutionalization of culture that produces a bottom-up emergence of resilience.

Ready to start your journey toward resilience? If so, Vetergy is ready also to help you navigate those waters!!

Find out how by contacting us here.

1200 Corporate Drive, Ste 170

1200 Corporate Drive, Ste 170©2025 Vetergy Group, LLC. All Rights Reserved.